William Brindley: Sculptor, Marble Merchant, Explorer

The Westminster Cathedral Marbles’, a fully

illustrated description and history of the

Cathedral decoration in colour is now

available from the Cathedral Gift Shop

or by post from the Cathedral Commercial

Manager.

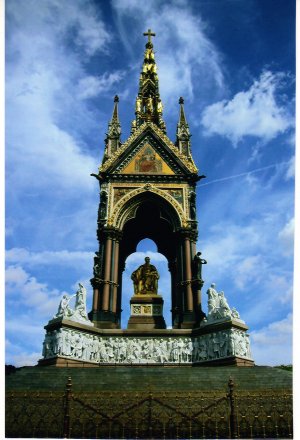

The Albert Memorial - stonecarving by William Brindley

Greek Verde Antico and Cipollino Columns in the north transept

of Westminster Cathedral - from quarries discovered by

William Brindley

by Patrick Rogers

Westminster Cathedral is not a conventional late-Victorian building but is modelled on a Byzantine basilica – built of brick with the interior decorated with marble and mosaics. The Cathedral authorities were unusually fortunate in having, just across the river, a marble merchant not only well-versed in Byzantine architecture but who knew where Byzantine materials could be obtained. His name was William Brindley.

William Brindley was born in Derbyshire in 1832 and, appropriately enough in a county renowned for its stone, became a stone carver. By the 1850s he was working for William Farmer, another stone carver from Derbyshire nine years his senior, on the decoration of churches and other buildings and in 1868 the two formed a partnership at 67 (later 63) Westminster Bridge Road. By this time they had become established stone and wood carvers and were the preferred choice of well-known architects such as George Gilbert Scott and Alfred Waterhouse. Scott chose Brindley for the capitals and other stone carving on the Albert Memorial in Hyde Park and described him in 1873 as “The best carver I have met with and the one who best understands my needs”.

George Gilbert Scott died in 1878 and William Farmer died the following year, leaving Brindley in sole charge of the firm. By this time the marble decoration of prestige buildings such as the Albert Chapel at Windsor, the Royal Mausoleum at Frogmore and the Opéra Garnier in Paris had convinced Brindley that coloured marble was becoming increasingly fashionable. So he embarked on a mission to seek out the old Roman quarries in Europe, Africa and Asia. As he put it 20 years later “As my delight is in old quarry hunting and as I knew the high price fragments dug up in Rome fetched, I determined to try to find the lost quarries and see if they were worked out or not”. After previously listing themselves in the Trades Directories simply as sculptors, in 1881 the Farmer & Brindley firm began to advertise as marble merchants.

During the 1880s and early 1890s Brindley travelled through Greece, Turkey and North Africa, discovering the ancient workings of Cipollino marble on the Island of Evia, Porta Santa on Chios, Verde Antico near Larissa on the central Greek mainland and Imperial Porphyry at Gebel Dokhan in the Egyptian Eastern Desert, which he travelled through with his wife, 19 Bedouin and 15 camels. Whenever possible his discoveries were followed by the negotiation of a concession to reopen the quarries and extract any workable marble. He also purchased examples of ancient marble which he discovered during his travels and produced a number of reports for the Royal Institute of British Architects, and trade journals such as ‘the Builder’. As a result of his research Brindley was elected a Fellow of the Geological Society in 1888.

Meanwhile demand for decorative coloured marble was increasing as Brindley had foreseen. There was a building boom in England and marble was in demand. A major customer was John Francis Bentley, the architect of Westminster Cathedral, who required 29 structural columns for the nave, aisles and transepts and large amounts of marble cladding for the

chapels. In 1899 Brindley invited visitors from the Cathedral to his works to watch the 13ft main nave columns being turned on lathes with steel blades, ground with sand and polished with oxide of tin before being installed in the Cathedral. The white Carrara capital for the top of each column, however, was only roughly shaped at the works and received its detailed carving after installation, two of Brindley’s stonemasons taking up to three months to carve each one.

Bentley died in March 1902 and Cardinal Vaughan, the Cathedral’s founder, followed him in June 1903 but work continued. The Cardinal had set his heart on eight 15ft Onyx columns to support the baldacchino (canopy) over the high altar. Both Bentley and Brindley had advised against onyx and, sure enough, when the columns arrived from Algeria four were already broken. So Brindley replaced them with Bentley’s choice of eight columns of yellow Verona marble. The baldacchino, which Bentley had described as “the best thing about the Cathedral”, was installed by Farmer & Brindley from 1905 and unveiled on Christmas Eve 1906. Then followed the marble of the Blessed Sacrament Chapel (completed 1907), Lady Chapel (1908), Sacred Heart Shrine and Vaughan Chantry (1910), Baptistry floor (1912), St Andrews Chapel (1915) and St Paul’s (1917).

Farmer & Brindley became a private limited joint stock company in 1905 when Brindley sold the firm for £50,000 (though retaining a majority shareholding) and transferred control to his nephew, Ernest Brindley, and his son-in-law, Henry Barnes. Now aged 74, Brindley moved down to Boscombe in Hampshire. He presented a major paper on the use of marble in architecture to the Royal Institute of British Architects in 1907 and continued to travel to distant countries such as Canada, the United States and Japan (three times). He corresponded with academics and architects, allowing them to consult his extensive architectural library and collection of photographs and he arranged for, and often led, groups such as the Architectural Association and the Geologists Association on tours of the Farmer & Brindley premises including its marble museum. He died in 1919 at the age of 87 leaving an estate valued at £60,000.

From 1908-28 Farmer & Brindley advertised as ‘Largest establishment and with greatest variety and stock of choice coloured marble and rare stones in the Kingdom’ but the 1914-18 War disrupted markets and Brindley’s death seemed to take the heart out of the firm. London’s County Hall and Glasgow’s City Council Chambers provided work until 1928 but the demand for wood, stone and marble decoration never picked up to pre-war levels. In the Cathedral the apse wall (1921), the organ screen (1924) and the south transept (1926) were clad with marble, while work on St Patrick’s Chapel, using some of Brindley’s last remaining stock, took place intermittently from 1923-29. But standards were starting to slip. There was an accident at the works in 1924 and in 1929 the carved marble screen at the entrance to St Patrick’s was rejected and had to be recarved. The same year, the year of the ‘Great Crash’, Farmer & Brindley went out of business. On its site at 63 Westminster Bridge Road a block of flats now stands.

First published in Oremus, the magazine of Westminster Cathedral October 2008

Enjoy more articles from the Cathedral’s magazine by subscribing to Oremus.